The battle for Le Mesnil-Patry, which proved so costly for the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and First Hussars, was part of a larger attempt to expand the Normandy beachhead. The Canadians, with 114 fatal casualties in what the Hussars call their “Charge of the Light Brigade,” were no harder hit than British divisions on either flank. The 51st Highland Division suffered heavy losses in the Orne River bridgehead, including an entire company of the 5th Black Watch. Both 50th Infantry and the 7th Armoured were roughly handled in the attempt to reach Villers-Bocage.

General Bernard Montgomery decided to pause in front of Caen, ordering General Sir John Crocker’s 1st British Corps, including the Canadians, to practice “aggressive defence” without risking large casualties. As overall ground commander, Monty ordered the Americans to push hard for Cherbourg while the British built up their forces and launched a new attempt to seize Caen.

Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, Britain’s outstanding tank general, was preparing Operation Epsom, a three-division attack designed to encircle Caen from the west. Epsom was delayed until June 26 partly because of the great storm of June 19-20 which wrecked the American Mulberry harbour, but also because Montgomery was torn between his desire to wait until he could stage a large-scale, set-piece attack and his fear that German reinforcements would arrive and force the kind of stalemate everyone remembered from the First World War.

The German high command was even more uncertain. Hitler and his propaganda machine had claimed they were eager to face and defeat the Allied invasion. Now that the Allies were safely ashore, the key question was whether a second landing would strike closer to Germany in the Pas de Calais region of Northern France. Hitler and his generals greatly overestimated the number of Allied divisions available. This belief was encouraged by reports from agents who were in fact controlled by the British. The German high command accepted intelligence estimates that General George S. Patton would lead a second amphibious assault north of the River Seine. Given this threat, future reinforcements for Normandy could only be drawn from distant theatres, Poland, Norway, and the south of France. The German 15th Army, a few hundred kilometres away, was to remain largely intact until August.

When Hitler met his generals in France on June 17 he expressed complete confidence and noted that the V-1 rocket attacks on London would soon demoralize the British. This, he insisted, was a more important goal than attacks on the British embarkation ports or the beaches of Normandy. Promises of greater air support were made, but the Luftwaffe proved incapable of challenging Allied tactical airpower, confining itself to nuisance night raids. Among German soldiers, the Luftwaffe was now a joke. “If it’s white it’s American, if it’s Black it is British, and if you cannot see it, it is the Luftwaffe.”

One result of the Hitler conference was the decision to transfer II SS Panzer Corps with 9 and 10 SS panzer divisions from Poland to Normandy. This powerful force began moving west just days before the Soviet Army began its summer offensive, operations which led to the collapse of Germany’s Army Group Centre and more than one million German casualties. There would be no more reinforcements for Normandy from the eastern front!

News of the movements of II SS Panzer Corps reached the Allies via Ultra, the top secret system of decoding German wireless messages. This prompted Montgomery to begin Epsom before more German armour arrived.

The start line for Epsom was a 12-kilometre stretch of countryside west of the Canadian position at Norrey-en-Bessin. Heavy bocage (hedgerows) on the right flank forced O’Connor to try to squeeze his three untried divisions, 15th Scottish, 43rd Wessex and 11th Armoured, through a relatively open kilometre-wide corridor leading down to the wooded valley of the River Odon. Once the river was crossed, a low, flat-topped ridge, known as Hill 112, dominated the battlefield and the southern approaches to Caen. Controlling that position would force the Germans to abandon the city.

The river was crossed and for several hours it appeared as if Hill 112 could be taken. However, the arrival of lead elements of II SS Panzer Corps, announced by Ultra, forced O’Connor to dig in and meet the enemy’s counterattacks.

The 3rd Canadian Division’s artillery supported O’Connor’s 8th Corps in the first phase of Epsom, and then prepared a fire plan for Operation Ottawa, an attack intended to secure the village of Carpiquet and its airport. As part of Epsom, Ottawa made a good deal of sense because the capture of the airport, and especially the southern hangars, would deny the enemy observation over the Odon bridgehead. But Operation Ottawa was cancelled when the scale of the German counterattacks prompted a new defensive role for the gunners.

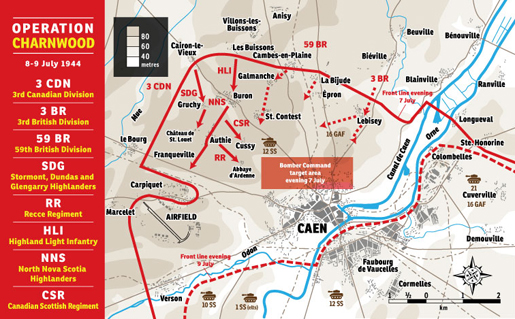

Once the enemy was beaten back, Ottawa became Operation Windsor, a 3rd Canadian Div. advance on Caen. This too was cancelled, and as Montgomery and General Sir Miles Dempsey, his army commander, made up their minds to stage Operation Charnwood—a new three-division frontal attack on Caen—Windsor became a separate operation to take place four days before the main attack. The 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade, with the Fort Garry Horse and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles under command, were to advance with the help of 500 guns from 21 regiments of artillery. The 16-inch guns of His Majesty’s Ship Rodney would soften up the defences with the help of two squadrons of Typhoons in support. Flails, Crocodiles and Petards, specialized armour from the 79th British Armoured Div., was also available.

All the impressive firepower allocated to Brigadier Ken Blackader’s brigade was poor compensation for a plan that defied both experience and common sense. Why order a single brigade into a salient allowing the enemy to focus on one small part of the front? Broad front attacks that split the enemy’s defensive fire had been advocated and employed since 1916 and there was no excuse for such attacks in 1944. To make matters worse, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, tasked to seize control of the hangars south of Carpiquet, were really fighting a separate, isolated battle.

At 5 a.m. on July 4, the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment and Le Régiment de la Chaudière began to advance across open fields. The barrage, timed to lift 100 yards every three minutes, was a classic First World War “creeper.” The Germans replied, as they had in 1917, by firing artillery and mortars just behind the advancing line of fire. Both battalions kept moving forward despite heavy casualties and the inevitable loss of men who simply could not get up and keep going. Major J. E. Anderson of the North Shores later described his experience:

“I am sure that at some time every man felt he could not go on. Men were being killed or wounded on all sides and the advance seemed pointless as well as hopeless. I never realized until Carpiquet how far discipline, pride of unit and, above all, pride in oneself and family can carry a man even when each step forward can mean possible death.”

The Chaudières, attacking in the centre, were spared much of the fire directed at the North Shores. The village was in ruins and the surviving Germans in the northern hangars were persuaded to flee or surrender by the first bursts of flame from the Crocodiles. The two battalions dug in under continuous fire. “Carpiquet was an inferno,” the Chaudières reported. “The bombardment was so intensive that hardly anyone dared leave the trenches and shelters.” At 11 a.m., the Queen’s Own Rifles moved towards Carpiquet, prepared to follow a new barrage to the control buildings on the far side of the airport. Blackader was under pressure from divisional commander Major-General Rod Keller who was in turn being pressed by the corps commander to continue an advance that would place the Queen’s Own at the very tip of a deep salient.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles attacking the south hangars were exposed to fire from the south side of the Odon as well as the airport. The Winnipegs advanced with only indirect fire support from tanks, as the single available squadron of the Garrys was also designated as armoured reserve. One troop was later sent forward with several flame-throwing Crocodiles to attack the bunkers, but in that open country, the tanks were vulnerable at long ranges, and two out of the four were quickly destroyed.

The Winnipegs were told to make a new effort with the remaining tanks, “executing a sweeping attack by the lower ground around the enemy’s left flank.” This manouevre was based on assurances that British troops from 43rd Wessex Div. had occupied Verson and could support the Canadian advance. The British apparently did briefly enter Verson, but this offered no defence against a counterattack from the southeast. The Garrys’ armoured sweep ran into a battle group of Panthers and was overwhelmed.

The enemy was unwilling to accept the loss of Carpiquet village and counterattacked from Franqueville shortly after midnight. The North Shores and Chaudières beat back all attacks, and at first light the artillery settled the issue, forcing the Germans to concede that the village could not be retaken. Canadian casualties in this operation, 365 of which 118 were fatal, made Operation Windsor one of the costliest brigade-level actions of the Normandy Campaign. The enemy, unwilling to settle for a defensive victory, also lost several hundred men, including a considerable number from the 3rd Battalion of 1st SS Panzer Div. which had been attached to 12th SS. Their attempt to overcome the North Shore Regiment’s defence of the north side of Carpiquet resulted in “considerable loses” to two companies who were “smashed” by artillery defensive fire, and North Shore small arms. The medium machine-guns of the Camerons of Ottawa were well positioned to deal with attacks from the north side of the salient and so they also had a major role in repelling the enemy.

Both sides conducted post-mortems on Carpiquet. The Germans concluded that the main Allied attack to take Caen would shortly follow. Rommel wanted to get the 12th SS Div. out of the city before it was completely destroyed, but only the supply and support units could be withdrawn. The 12th SS would have to face one more onslaught from fixed defensive positions.

The Canadian response to Carpiquet was to circulate a “lessons learned” review, which included an implicit critique of the plan for Operation Windsor. The brigade noted that on a battlefield where a well-entrenched enemy employed a series of interlocking defensive positions, and relied on “large concentrations” of observed fire from mortars, “attacks must be launched on a broad front” simultaneously so that the enemy “cannot fire in enfilade from localities not being attacked.” Broad front attacks, the report added, would also split the enemy’s defensive fire.

This was not the kind of common sense British senior commanders wished to hear in 1944. Crocker, who had made a series of dubious decisions as a corps commander, blamed the Canadians for the “failure” of Carpiquet. On July 5, before the full outcome of the battle was known, Crocker sent a letter to the Army Commander, General Miles Dempsey, claiming that the limited success of Windsor was due to lack of control and leadership from the top.

“Carpiquet,” he wrote, “proved to me conclusively” that the divisional commander, General Keller, “is not fit to command.” Both Dempsey and Montgomery endorsed this view despite a growing awareness that all three infantry divisions in Crocker’s corps were highly critical of his willingness to order a series of isolated brigade or battalion actions. The 3rd British Div. was particularly bitter about the struggle for Chateau de la Loude which they described as “the bloodiest square mile in Normandy.” The historian of 51st Highland Div. described the sense of relief everyone felt when the division left 1st British Corps.

The Carpiquet battlefields are largely intact. The town, which was pretty well destroyed, is much larger today and the airport modernized, but if you stand outside the Aero Club at the western end of the airfield much can be seen and understood. On one of our battlefield tours Lieutenant-General (retired) Charles Belzile, who was then President of the Canadian Battlefields Foundation and Honorary Grand President of The Royal Canadian Legion, was asked how would NATO armies take Carpiquet today? He paused and said, “Well not in isolation and not with infantry across such open ground.”

- Banner photo: Allied officer examine a damaged German aircraft at Carpiquet airport in Normandy, July 1944. Credit: Ken Bell, Library and Archives Canada.

- Originally published in Legion Magazine on March 28, 2011.